Saha ionization equation

The Saha ionization equation, also known as the Saha–Langmuir equation, was developed by the Indian astrophysicist Meghnad Saha in 1920, and later (1923) by Irving Langmuir. One of the important applications of the equation was in explaining the spectral classification of stars. The equation is a result of combining ideas of quantum mechanics and statistical mechanics.

For a gas at a high enough temperature, the thermal collisions of the atoms will ionize some of the atoms. One or more of the electrons that are normally bound to the atom in orbits around the atomic nucleus will be ejected from the atom and will form an electron gas that co-exists with the gas of atomic ions and neutral atoms. This state of matter is called a plasma. The Saha equation describes the degree of ionization of this plasma as a function of the temperature, density, and ionization energies of the atoms. The Saha equation only holds for weakly ionized plasmas for which the Debye length is large. This means that the "screening" of the coulomb charge of ions and electrons by other ions and electrons is negligible. The subsequent lowering of the ionization potentials and the "cutoff" of the partition function is therefore also negligible.

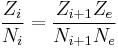

For a gas composed of a single atomic species, the Saha equation is written:

where:

is the density of atoms in the i-th state of ionization, that is with i electrons removed.

is the density of atoms in the i-th state of ionization, that is with i electrons removed. is the degeneracy of states for the i-ions

is the degeneracy of states for the i-ions is the energy required to remove i electrons from a neutral atom, creating an i-level ion.

is the energy required to remove i electrons from a neutral atom, creating an i-level ion. is the electron density

is the electron density is the thermal de Broglie wavelength of an electron

is the thermal de Broglie wavelength of an electron

is the mass of an electron

is the mass of an electron is the temperature of the gas

is the temperature of the gas is the Boltzmann constant

is the Boltzmann constant is Planck's constant

is Planck's constant

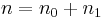

In the case where only one level of ionization is important, we have  and defining the total density n as

and defining the total density n as  , the Saha equation simplifies to:

, the Saha equation simplifies to:

where  is the energy of ionization.

is the energy of ionization.

The Saha equation is useful for determining the ratio of particle densities for two different ionization levels. The most useful form of the Saha equation for this purpose is

,

,

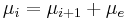

where Z denotes the partition function. The Saha equation can be seen as a restatement of the equilibrium condition for the chemical potentials:

This equation simply states that the potential for an atom of ionization state i to ionize is the same as the potential for an electron and an atom of ionization state i+1; the potentials are equal, therefore the system is in equilibrium and no net change of ionization will occur.

In the early twenties Ralph H. Fowler (in collaboration with Charles Galton Darwin) developed a very powerful method in statistical mechanics permitting a systematic exposition and working out of the equilibrium properties of matter. He used this to provide a (rigorous) derivation of the ionization formula which as described earlier Saha had obtained by extending (and justifiably) to ionization of atoms the theorem of Van 't Hoff, well known in physical chemistry for its application to molecular dissociation. Also, a significant improvement in the Saha equation introduced by Fowler was to include the effect of the excited states of atoms and ions. Further, it marked an important step forward when in 1923 Edward Arthur Milne and R.H. Fowler in a paper in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society showed that the criterion of the maximum intensity of absorption lines (belonging to subordinate series of a neutral atom) was much more fruitful in giving information about physical parameters of stellar atmospheres than the criterion employed by Saha which consisted in the marginal appearance or disappearance of absorption lines. (The latter criterion requires some knowledge of the relevant pressures in the stellar atmospheres, and Saha following the generally accepted view at the time assumed a value of the order of 1 to 0.1 atmosphere.) To quote from E. A. Milne:

"Saha had concentrated on the marginal appearances and disappearances of absorption lines in the stellar sequence, assuming an order of magnitude for the pressure in a stellar atmosphere and calculating the temperature where increasing ionization, for example, inhibited further absorption of the line in question owing to the loss of the series electron. As Fowler and I were one day stamping round my rooms in Trinity and discussing this, it suddenly occurred to me that the maximum intensity of the Balmer lines of hydrogen, for example, was readily explained by the consideration that at the lower temperatures there were too few excited atoms to give appreciable absorption, whilst at the higher temperatures there are too few neutral atoms left to give any absorption. ..That evening I did a hasty order of magnitude calculation of the effect and found that to agree with a temperature of 10000° [K] for the stars of type A0, where the Balmer lines have their maximum, a pressure of the order of 10-4 atmosphere was required. This was very exciting, because standard determinations of pressures in stellar atmospheres from line shifts and line widths had been supposed to indicate a pressure of the order of one atmosphere or more, and I had begun on other grounds to disbelieve this."[1]

See also

References

- ^ "Meghnad Saha". http://www.saha.ac.in/cs/archive.mns/index.php?pg=8. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

External links

- Derivation & Discussion by Hale Bradt

- A detailed derivation from University of Utah Physics Department

- Lecture notes from University of Maryland Department of Astronomy

- Saha, Megh Nad; On a Physical Theory of Stellar Spectra, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A, Volume 99, Issue 697 (May 1921), pp. 135–153

- Langmuir, Irving; and Kingdon, Kenneth H.; The Removal of Thorium from the Surface of a Thoriated Tungsten Filament by Positive Ion Bombardment, Physical Review, Vol. 22, No. 2 (August 1923), pp. 148–160

![\frac{n_{i%2B1}n_e}{n_i} = \frac{2}{\Lambda^3}\frac{g_{i%2B1}}{g_i}\exp\left[-\frac{(\epsilon_{i%2B1}-\epsilon_i)}{k_BT}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2484702b34c60d1531ca30548fc34e19.png)

![\frac{n_e^2}{n-n_e} = \frac{2}{\Lambda^3}\frac{g_1}{g_0}\exp\left[\frac{-\epsilon}{k_BT}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/427932d7b2eda4f33f7bb24517ff820c.png)